Levels of Abstraction

Abstraction is a taste.

Specifically, taste is required when you need to choose the right level of abstraction when presenting something. Abstraction is the process of removing characteristics from something in order to reduce it to a set of essential characteristics. This discernment is based on personal preference and experience, and so, there isn’t a universal standard for what constitutes good or bad abstraction. But with taste, you can tell what’s clearly good or what’s completely shit.

Since I’ve been thinking about things like taste and abstractions lately, I remember watching one of the greatest tech talks I’ve ever seen on this very topic many years ago. It was a talk given by Cheng Lou, a former member of the React team entitled “On the Spectrum of Abstraction”. It’s just a tad over 30 minutes, but it’s mind-blowing. The ideas on abstraction that Lou presented is as relevant today as it was almost 10 years ago when the talk was given at React Europe 2016. I’ve embedded the video below and I encourage you to watch or re-watch it.

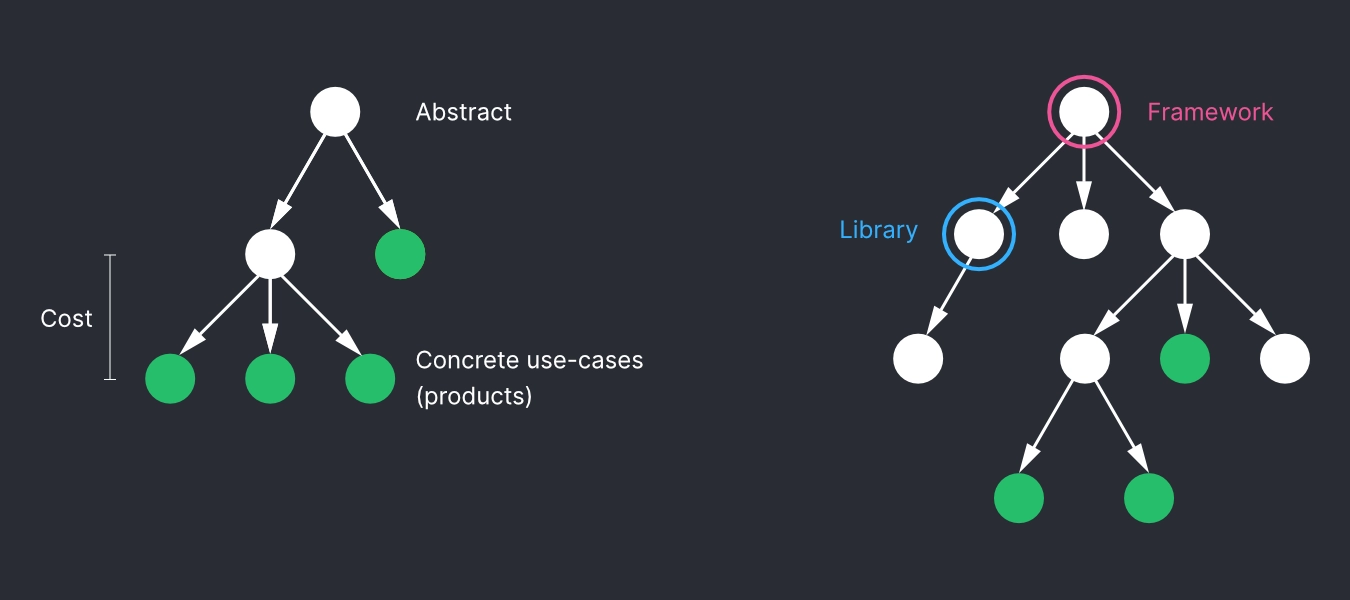

Lou presented the idea of the levels of abstractions as a tree structure. I’ve recreated some of his key diagrams below to aid my summary. At the top of the tree you are dealing with the very abstract. As you descend down the tree, you move closer to your concrete (immediately useful) use-cases which are represented by the green “leaf” nodes.

Fig.1: Levels of abstraction as a tree structure.

In the software development world, the top node can be an abstraction like a framework, e.g. React or AngularJS. Moving down the layers means incorporating specific plugins or libraries to fulfil certain features. The end goal of developers is to reach the leaf nodes, which are the actual products/apps that the software engineers want to deliver to their customers or clients.

Note that at the bottom leaf nodes, you have products that are supposedly devoid of any abstractions for the users to tranverse. The products should “just work”, and thus, “immediately useful”. That’s what is meant by having “concrete use-cases”.

Also note that there are inherit costs in traversing up and down the layers. When you move up the tree, you remove specific features in order to generalize a particular idea. The consumer of a higher layer of abstraction must pay for its use, i.e. moving down to the concrete use-cases. This cost could be either mental energy or actual development effort.

Although the talk is very software focused, particularly when it discusses the JavaScript ecosystem and its plethora of libraries and frameworks, the idea of “levels of abstraction” can extend well beyond it.

Think of art. An artist painting a portrait must think in abstractions. The painter must decide on the style to paint the subject: from abstract to impressionist to realism.

Take the two different painting styles below for example. One style use fewer brush strokes and less colors to portray a certain imagery. The other style is almost photo realistic and requires painstaking attention to detail to recreate reality. The artists’ abstractions are deliberate and are meant to convey different messages.

Fig.2: Levels of abstraction in art. On the left is Edouard Manet's "Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets" in an impressionist style. On the right is a hyper-realistic painting from Leng Jun, entitled "Mona Lisa."

Going back to taste. Lou in his talk also stressed the importance of choosing the “right” level of abstraction. He notes: if you get your abstractions wrong, if you create your library wrong, or if you target your product wrong, you will lose your adopters—your customers.

“Lots of problems arise from a bad understanding of where we should be in the levels of abstraction.” –Cheng Lou

Amen, brother. What Lou preached a decade ago is essentially about taste. It’s a skill that is just as relevant today as it was ages ago. I believe it is an evergreen skill, even in our age of AI.